What ‘AI-native engineering’ actually looks like inside our team

- Max Honcharuk

- Dec 22, 2025

- 7 min read

Inside our team, AI-native engineering did not start with a bold mandate or a full rewrite of our software development lifecycle. It started with experiments, skepticism, broken demos, messy code reviews, and long conversations about what “good engineering” even means when a non-human can write half your code. This is what AI-native engineering actually looks like for us — not as a concept, but as a working process.

In this article, I’ll guide you on how our team approaches AI-native engineering. And I’ll start with a brief recap of the AI coding workshop I recently held.

From scripted demos to controlled chaos

Over the last few months, I’ve been running AI coding workshops focused on IDE and CLI agents. Unlike traditional engineering sessions with scripted demos, these workshops functioned as live experiments. In a single 1.5-hour session, we built a new feature end-to-end — from UI mockups to database persistence — clearly showing how AI-native development works in practice.

AI quickly proved to be an active participant in the process, not just a passive tool. Because agents don’t produce the same output twice, predictable demos weren’t possible. Instead, sessions required constant adjustment: refining prompts, debugging AI-generated logic, and analyzing why solutions partially succeeded or failed.

While the agent was working, we focused on techniques that help engineers control quality and expectations, including:

Reducing hallucinations in smart autocomplete;

Switching between architect, planner, and developer modes;

Delegating well-defined tasks instead of full ownership;

Configuring behavior through system instructions and specs;

Applying strict review and validation practices.

As a result, the developer’s role shifted away from pure implementation toward supervision and design. Engineers spent more time reviewing outputs, identifying risks, and deciding when to intervene. AI accelerates delivery, but every critical decision still requires human validation — making this shift in responsibility a core trait of AI-native engineering.

Seeing AI work — then choosing whether to believe it

Reactions to AI tools inside engineering teams tend to split quickly.

Some developers treat AI as almost magical, while others remain skeptical — even after seeing it work live — and notably, even convinced engineers don’t immediately change their habits.

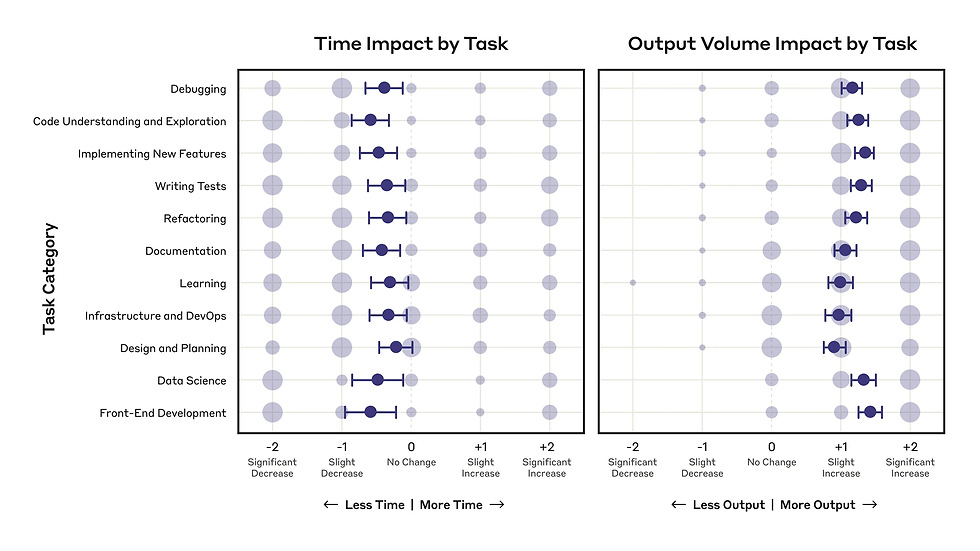

This mirrors findings from a recent randomized controlled trial, where experienced open-source developers using early-2025 AI tools actually took 19% longer to complete tasks, despite strongly believing AI was speeding them up. The gap between perception and reality is striking: developers expected a 24% speedup and still believed they were faster even after measurable slowdowns.

That said, other research showed that developers who use tools like Claude across a large share of their work reported productivity gains, achieving a 50% performance boost, translating into a 2-3x increase.

A meaningful portion of AI-assisted work also falls into categories that wouldn’t exist otherwise — exploratory tasks, internal tools, or scaling efforts that weren’t previously cost-effective.

This exposed a core misconception we encountered early on — giving teams AI tools does not equal AI adoption, and without shared practices, guidance, and validation, AI becomes an inconsistent utility rather than a real productivity lever.

Gradual adoption: from skepticism to structure

Our adoption of AI followed a clear progression: POC → Pilot → Accelerator → R&D. Each phase addressed a different risk, from trust to scale to long-term maintainability. This gradual approach helped prevent disruption while allowing teams to adapt meaningfully.

Phase 1: Proof of Concept — speed without trust

The first step was intentionally modest. We aimed to build a UI for an existing API as quickly as possible using Cursor and v0. At that point, expectations were low due to earlier mixed experiences with AI tools that caused more confusion than value.

Then results arrived faster than anticipated. One developer completed the first page in a day, and within a week, the entire UI was built. That moment wasn’t just about speed — it clearly demonstrated that development workflows themselves were changing.

What shifted wasn’t belief in the tool, but belief in the direction. Software development had crossed a threshold, and ignoring that would have been a mistake.

Phase 2: Pilot — shared knowledge exposes shared problems

Next, we invited engineers from other projects to try the same approach. Rather than introducing strict rules, we shared examples of what worked and encouraged experimentation. Adoption spread naturally.

Within weeks, the team identified 13 specific use cases where AI tools added measurable value. However, scaling also surfaced problems that hadn’t appeared earlier. Code styles varied more, reviews took longer, and skipping reviews led directly to bugs.

This made one thing obvious: AI adoption requires training and process alignment, not just access to tools. Without structure, AI amplifies inconsistency instead of productivity.

Phase 3: Engineering Accelerator — learning before scaling

To address these issues, we introduced AI coding agents into our Engineering Accelerator. This environment allowed engineers to experiment safely while focusing on best practices, not just speed.

Engineers who treated AI as a skill rather than a shortcut consistently performed better. In one controlled comparison, an AI-enabled engineer completed tasks 60% faster than a peer without AI. However, speed came with trade-offs.

AI-generated solutions are often introduced:

new architectural approaches,

unconventional project structures,

increased maintenance complexity if not reviewed carefully.

This is where many engineers become cautious — and rightfully so. AI-native engineering doesn’t ignore these risks; it builds processes to mitigate them.

Phase 4: R&D — discipline at scale

The final phase focused on balance. Today, our team actively uses tools such as:

Cursor

Claude Code

Lovable

But tools are only part of the picture. What enables consistent quality is a growing set of internal .md specifications that guide how AI tools operate. These documents define architectural standards, naming conventions, constraints, and review expectations.

By embedding engineering discipline into prompts and workflows, AI becomes a compliant accelerator rather than an uncontrolled generator. This system is still evolving, but it allows us to scale AI usage without sacrificing quality.

Measuring reality: AI vs traditional development

To move beyond intuition and hype, we ran a controlled internal experiment. Two engineers built the same product — a task manager with Slack integration — under identical conditions. The PRD, stack, scope, and deadlines were all the same. The only difference was how the work was done.

One engineer followed a traditional workflow. The other relied heavily on AI tools, including Claude Code, ChatGPT, and smart autocomplete. We tracked every phase of delivery to identify where time was saved or lost: planning, setup, development, testing, deployment, and documentation.

The outcome was clear:

traditional development: 99 hours

AI-assisted development: 41 hours

That nearly 60% improvement wasn’t evenly distributed, though. The real value came from understanding where AI helped and where it introduced friction.

Phase | With AI (h) | Without AI (h) | Savings (%) | Claude Code usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Planning | 2 | 4 | 50 | Acceptance criteria, Slack message template |

Setup | 4 | 7 | 43 | Dockerfile, docker-compose, GitHub Actions config |

Development | 23 | 61 | 62 | Frontend (UI/UX, business logic), backend (API, models, database, authentication), Slack integration, bug fixing |

Testing | 2 | 8 | 75 | Unit tests (API, app layer, domain layer, infrastructure, components, effects, services), storybook setup |

Deployment | 6 | 9 | 33 | Terraform scripts and deployment configs (ECS, Load Balancer, CI/CD), infrastructure design and environment setup. |

Documentation | 4 | 10 | 60 | Project docs (Claude.md, conventions, patterns) |

Total | 41h | 99h | 59% | saved with Claude Code |

Where AI accelerated the process:

Backend logic creation

Architectural scaffolding

Test generation

These areas benefited from AI’s ability to work quickly across patterns and abstractions.

Where AI hit limits:

UI consistency (misinterpreting mockups)

Cross-layer integration (misaligned enums, endpoints, contracts)

Long sessions, where context degradation caused errors

This experiment reframed how we think about AI tools. They are not general-purpose replacements for engineers. They are force multipliers in specific phases of the SDLC, and liabilities in others. AI-native engineering means designing processes that expect these strengths and weaknesses.

Also read: Two Radency engineers built the same MVP, with and without AI — learn more about our experiment on AI-assisted vs traditional development.

How AI changes the engineers’ role

Across every phase, one pattern stands out clearly. AI does not remove the need for engineering judgment — it intensifies it. Engineers spend less time writing boilerplate and more time thinking critically.

Today, effort shifts away from execution toward:

setting constraints,

supervising outputs,

reviewing and correcting assumptions.

AI-native engineering isn’t about writing less code. It’s about making better decisions faster and knowing when not to trust what the machine produces.

AI Tool Adoption at Radency

At Radency, we incorporate AI tools into every project as a standard part of our development process.

Primary Tools

→ Cursor - 53% adoption

Cursor is our dominant tool, used in both autocomplete and agentic modes. After a year of adoption, it has become the first stop across most of the tech stack. Teams rely on it for day-to-day coding tasks as well as broader SDLC activities such as design, DevOps, and code review.

→ GitHub Copilot - 24% adoption

GitHub Copilot has the longest history of adoption among our AI coding tools and was the first stop for many teams. Over time, however, technical limitations and missing functionality have led to a gradual decline in usage, with teams increasingly switching to other tools. This shift accelerated after reductions in suggestion quotas.

→ Claude Code - 23% adoption

With only six months of adoption, Claude Code has already become the primary tool in nearly a quarter of our projects. Its share continues to grow, driven by accuracy and efficiency.

→ Other tools

We have also tested tools such as RooCode, Warp, and Gemini CLI internally. While promising in specific scenarios, they currently show lower adoption across active projects.

Maturity of AI Usage

After a year of experimentation, all projects have moved beyond the initial phase of tool selection and configuration. In approximately 20% of projects, teams explicitly define AI-related tasks and delegate them to agents. Only a small subset of teams build applications in a fully agentic way, spending most of their time reviewing and refining generated code.

Impact on Productivity

Based on our internal survey, most teams report a productivity increase of 10-20%. In small startup environments, the impact can be significantly higher - in some cases reaching up to 50%, as AI generates a substantial portion of the solution.

What AI-native engineering is (and isn’t)

As a brief conclusion, I suggest the following table:

AI-Native Engineering Is | AI-Native Engineering Is Not |

|---|---|

Built around AI’s real strengths and limits | Letting AI handle everything |

Measured through experiments, not assumptions | Prioritizing speed over correctness |

Adopted gradually, not imposed abruptly | Replacing fundamental engineering practices |

Governed by shared standards and structured reviews | Ignoring quality and long-term maintainability |

Driven by engineers’ judgment and decision-making | Driven by tools instead of people |

The biggest mistake teams make is confusing AI usage with AI-native practice. Real adoption is cultural, procedural, and technical at the same time.

Wrapping up

AI-native engineering inside our team isn’t finished or fixed. It’s an evolving system shaped by experiments, failures, and measurable wins. What’s clear is that AI-augmented delivery works — and the efficiency gains are real. It enhances learning by focusing humans on business goals, trade-offs, and pitfalls rather than routine typing.

However, the lasting value doesn’t come from novelty or raw speed. It comes from intentional process design that respects both engineering discipline and AI capability. That balance is where AI-native teams are truly built.

If you want to strengthen your project with AI-savvy engineers, contact us.